All About Milkweed

Protection by Toxicity

Milkweed in the Wild

Milkweed in the Garden

The Controversy about Tropical Milkweed

Milkweed and Aphids

Protection by Toxicity

The monarch butterfly has evolved in close association with milkweed species; their larvae do not feed on plants from any other genera. For most animals, the milkweed plant is far from appetizing: it contains toxins called cardenolides that can make creatures vomit and, should they ingest enough, cause their hearts to beat out of control. Monarch caterpillars, however, devour milkweed. In fact, it’s the only thing they will eat. They are protected by genetic adaptations that cancel out the harmful effect, thereby providing them with a special food source that others shun, as well as a way to repel predators by storing the toxin in their bodies. In addition, the bright colors—varied combinations of orange, yellow, black and white—of both the larva and the butterfly, are warning colorations that alert potential visual predators like birds to their toxicity.

The adult form of the insect (technically called the imago) will seek out new territories and new stands of host plants during the spring dispersal. Breeding sites can vary from year to year, probably to avoid or confuse predators and parasitoids, but somehow the females seem to know where the herbaceous milkweeds will reappear. There are also theories that the frass (insect droppings) left around stands of milkweeds that have successfully supported larvae, leave a trace that females can detect.

The level of cardenolides varies with each species and, of all the milkweeds, A. curassavica has one of the highest levels of toxicity. The monarch butterfly is a tropical species and it most likely co-evolved with the tropical milkweed, which may mean that it is actually the best host plant for the larvae of the monarch butterfly. The adult female is able to take a chemical reading of a plant before she lays her eggs on it: the higher the level of toxicity, the more protection her offspring have!

There are about one hundred species of milkweed in America and they all produce toxic cardenolide compounds, the levels of which vary from one species to another. Therefore, so does the toxicity of the larvae, depending on which milkweeds they were feeding on. These toxins are ingested only in the larval stage, sequestered within the body of the larva, and then passed on to the adult form during the pupal stage. Scientists can do cardenolide fingerprinting tests to determine which milkweed species the larvae had been feeding on and if these host plants are geographically consistent. I have a lot of faith in the balance of nature’s boom and bust cycles, especially with insect species that are not unnatural, so if and when the monarch populations resurge in California, perhaps these tests will help scientists determine where the butterflies are coming from.

A research professor of zoology, Dr. Lincoln Brower, and his wife were very interested in the shared toxicity of the monarch butterflies and the plants their larvae fed on. They worked with birds, which are primarily visual predators, to understand how the chemical toxicity protected the butterflies. They discovered that it is a learned response so it does not necessarily protect an individual, but offers protection to the whole population. Other butterfly species like the red admiral (a non-toxic species) have evolved to take advantage of the monarch coloration patterns, mimicking its coloration for protection.

Milkweed in the Wild

Asclepias, or milkweed species usually grow in grassland habitats. Here in Marin, much of it has been eradicated from areas where cattle have been pastured. I’ve only found populations of narrow-leaf milkweed (A. fascicularis) growing naturally in two places in Marin: at Sky Oaks, in the meadow close to the boundary of the Meadow Club, and in scattered clusters on Mt. Burdell, fairly close to the largest of the serpentine outcrops. Because milkweeds are poisonous plants, most browsing and grazing animals avoid it, which also means that it is a deer proof plant.

When I’m camping during the summer in Sonoma, Mendocino and Lake Counties, I do find stands of other species of milkweeds: A. speciosa, A. eriocarpa, and A. cordifolia, as well as narrow-leaf milkweed. A. fascicularis seems to prefer growing in ephemerally wet places, such as close to small seasonal streams, and at the seasonally wet edges of ponds and lakes. As summer progresses, these conditions become drier, but the milkweeds are thriving in large stands. Indian milkweed (A. eriocarpa) grows in large drifts in hot, dry conditions in an open exposed meadow close to Lake Pillsbury at about 1,800 feet elevation, but purple milkweed (A. cordifolia) wants a bit of shade, so I find it growing at the base of shrubs or on north facing slopes. I’ve collected seed from the wild species, but had no luck so far in growing viable plants from those seeds!

Showy milkweed (Asclepias speciosa) is a beautiful plant in bloom, with large fragrant clusters of pink-tinged white flowers. I see it growing in ditches, sometimes even along roadsides, and at higher elevations. It will grow in a garden though it is often difficult, and can take years to get established. Then, once the plant takes hold, it will quickly run by rootstock to take over a bit of ground.

Since milkweed is scarce in Marin, habitat gardeners really can help monarch populations by including milkweeds in their gardens. I grow three different species in my Novato garden: showy milkweed, narrow-leaf milkweed, and Mexican milkweed (also called tropical milkweed, or bloodflower).

Milkweed in the Garden

Milkweeds are herbaceous perennials, dying back to thick fleshy rootstocks during the colder months. Showy milkweed (Asclepias speciosa) has roots that wander, and will eventually spread out to where they want to grow. This species is very appreciative of water during the summer months and will respond with vigorous, spreading growth and lots of beautiful flowers. It did beautifully in a garden I built that included a small pond with a seep. Showy milkweed spread toward the moisture of the seep and created a drift that was spectacular and powerfully fragrant when in bloom!

Narrow-leaf milkweed (Asclepias fascicularis) is a better choice for a drought-tolerant garden, where it needs full sun, good drainage, and perhaps a little extra water during the hottest months. However, I soon discovered an idiosyncrasy: this plant wants to choose where it will grow! It reminds the habitat gardener that they don’t have total control over the garden. It seems to establish best where it seeds itself. Over the years, I’ve planted out healthy, vigorous specimens only to watch them fade and die after just a season or two. By that time the seeds have been blown about the garden, and new seedlings appear in various places where they persist and thrive year after year! Narrow-leaf milkweed has no problem with frosty nights, keeping its leaves long after showy milkweed is nothing but bare stems. Leaves are eventually shed, and then I cut it right back to its base, as much to invigorate new growth on the plants as to try to break the cycle of the dreaded orange aphid.

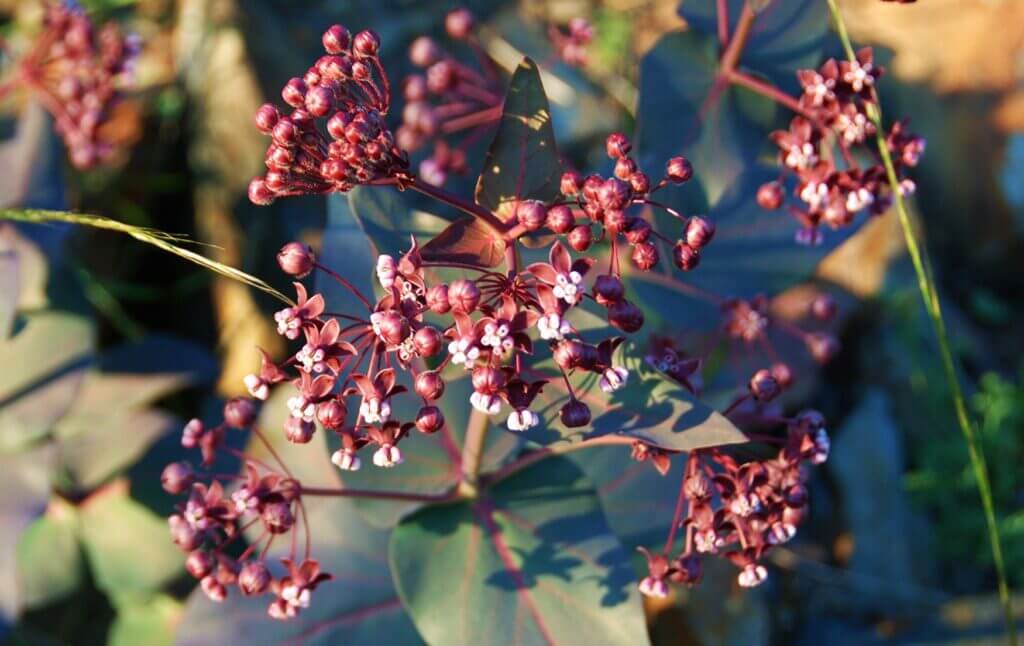

Asclepias curassavica is native to Mexico. It is a tropical plant and, as such, is frost tender. In very cold areas it is grown as a summer annual. Seeds germinate readily, especially if the seed is pre-soaked and the seed starting flat is placed over bottom heat. In many ways this is the best of all milkweeds for the garden; it is fast growing, with lots of orangey-red flowers that attract pollinators. There are also hybrids: ‘Silky Red’ with deep red flowers, and ‘Silky Gold’ with clear yellow flowers.

Mexican or tropical milkweed also grows beautifully in large containers. When grown in a pot, it is also easier to move it to a protected site for the colder months. This milkweed is also the best one to use for raising larvae under controlled conditions. Plants can be grown to a good size in a 4” pot and will still fit into a terrarium that contains the developing larvae. Asclepias curassavica also has the perfect level of the toxins that both the larvae and adults need to protect themselves against visual predators.

The Controversy about Tropical Milkweed

Because the numbers of California monarchs at over-wintering sites in recent years are greatly reduced, everyone seems to want a scapegoat to blame. Tropical milkweed is taking a lot of blame for two main reasons: it does not necessarily die back in frost-free environments, and it sometimes hosts a protozoan parasite (Ophryocystis elektroscirrha) that can infect and kill the butterflies in both the larval and adult stages.

Populations of this parasite were first noted on monarchs in Florida in the 1960’s and on plants, mostly tropical milkweed, which thrives in the mild, mostly frost-free climate in Florida. Populations of the OE parasite can persist on plants that stay evergreen season after season. The OE parasite is also on herbaceous native milkweed species, but since these species die back every year, populations of the parasite do not build up.

The parasite is transmitted to the adult butterfly in three different ways:

Larvae feeding on the infested plants will ingest spores of OE parasites that penetrate the gut wall and replicate in the hypoderm, and are present during pupation. During the pupal stage, the spores of the parasite form on the wings of the adults.

Infected males can infect females with the spores during mating.

Females, either infected during pupation, or during mating, can drop these spores while ovipositing, both on the leaves of the plants and on their own eggs.

Larvae that are infested but manage to pupate, often become adults which have difficulty eclosing from the pupa; they can’t expand their wings properly and therefore can’t fly and don’t survive. Adults that do manage to eclose and expand their wings for flight can have dormant OE spores in the scales of their wings and on the abdomen. These spores can drop off on plants, or onto another butterfly during mating. Studies have shown that the non-migratory populations have the highest infection rates, and the populations with the longest migrations have the lowest rates of infection for OE parasites.

The control method is fairly simple. It’s up to the gardener to treat the tropical milkweed as if it were an herbaceous perennial! In the fall months, October thru November, when the showy milkweed has already gone completely dormant, and the narrow-leaf milkweed is becoming dormant, it’s time to cut the tropical milkweed plants down to the ground, thereby forcing them into dormancy. This will help solve two perceived problems associated with this plant: one, that it will encourage late season mating and laying of eggs, and two, that it will infect the butterflies with the OE parasite.

Ecofriendly Gardeners Beware! Since the plight of the monarchs has become a popular issue and large commercial nurseries are now growing and selling milkweeds (usually always the showier eastern or tropical species), the ecofriendly gardener needs to confirm that no neonicotinoids were used on the plants they are purchasing. Neonicotinoids are systemic insecticides derived from nicotine that are deadly to all sucking and chewing insects, which includes caterpillars (and the dreaded oleander aphid). Large growers do not take the time to control pests organically, but they do know that customers won’t buy the milkweeds if they see them infested with aphids. Small, dedicated growers do not use systemic insecticides, but manually control the populations of insect pests.

Orange aphids (Aphis nerii) on tropical milkweed. Don’t let the colonies build up like this! Photo: Marc Kummel

All milkweeds have a white latex sap, hence the common name. Photo: Marc Kummel

Milkweed bugs over-winter at the plant roots and start to feed on the seedpods as they mature. Photo: Marc Kummel

Milkweed and Aphids

In my garden and at the nursery, most larvae show up on the Mexican milkweed. But so does the orange oleander aphid (Aphis nerii). The family Asclepiadaceae, to which the milkweeds belong, includes a very common landscape (and freeway) plant, the oleander (Nerium oleander). It is native to the Mediterranean region and has been introduced to California where it thrives in difficult situations.

Introduced along with the oleanders, unfortunately, came a species of aphid (Aphis nerii) that is a specific pest on plants in the milkweed family. As so often happens with non-native introduced species, the natural controls on the populations of this species of aphid have been left behind.

Aphids are “true” bugs that feed on plant fluids with sucking mouthparts. The usual predators of aphids—ladybird beetles, both adults and larvae, lacewing larvae, and syrphid fly larvae, can’t do a really good job of keeping this aphid in check because of the milkweed toxins. The oleander aphid is also toxic (it is orange as a warning) and I’ve read that beetle and lacewing larvae that have fed on these aphids are sometimes malformed as adults. The toxins are also in the aphid’s exudate (commonly called honeydew) so even the ants aren’t interested in tending these aphid colonies. Tiny wasps (braconidae) do parasitize the aphids, turning them into aphid “mummies,” and that does help to keep populations at somewhat manageable levels.

Aphids have extremely interesting and varied reproductive strategies (parthenogenesis), which could more simply be described as cloning. There are hundreds of different species of aphids and many variations on the life cycles; some have males with wings and they mate with females that will lay eggs at the end of one season and then over-winter to the next season. Not so with the orange oleander aphid, which shows up on milkweeds as soon as new growth starts in spring!

The oleander aphids rarely produce males so females do not lay eggs. Instead, the colonies quickly form from stem mothers: females that have over-wintered at the base of the plants. These are pregnant females that immediately give live birth to other already pregnant females. In this way huge colonies can form in no time! Winged females are produced occasionally and they are able to fly to a new feeding site and begin producing large new colonies.

I have found that the best way to control the aphids is to find them early before big colonies develop. Luckily, here in Marin, most of the monarchs arrive in late summer so there is time to deal with the aphids without worrying about damaging butterfly eggs or larvae or beneficial predators, and still have vigorous host plants growing when the monarchs do arrive.

A gardener growing milkweeds for the larvae of the monarchs must keep the aphid colonies under control, otherwise the aphids can enervate a plant. A milkweed plant that is supporting large, dense colonies of aphids is much less desirable to the female monarch searching for a host plant on which to lay her eggs.

My Strategies for Control:

First, I simply use a strong spray of water and my fingers to crush and remove the small initial colonies.

Second, I’ll use a castile soap spray on colonies that aren’t being controlled by just knocking them off the plants.

Third, if stems are inundated by aphids, I will cut them out and put them in the trash can to be removed from my property. Sometimes I cut only the top half of the stem where the aphids have congregated; the plants respond by sending out lateral shoots and more flowering stems.

Fourth, if colonies still persist I’ll use a Neem oil spray to kill them, but be aware that the oil spray can also kill caterpillars and other soft-bodied beneficial insects. It is not harmful to bees, butterflies, beetles, birds, mammals, or earthworms and other creatures in the soil.

Fifth, in the fall, when these herbaceous perennials die back, I cut out all the old stems, clean up at the base of each plant, and apply a sprinkling of Neem seed meal. The intention is to kill off the over-wintering stem mothers.

Neem seed oil comes from the Neem tree (Azadirachta indica), a native of India, and the seed meal is a by-product of the oil extraction. It is a vegetable oil with triglycerides and many triterpenoid compounds. The oil is a bioinsecticide and acts as a deterrent to feeding (phagorepellent), which repels a variety of soft-bodied, sucking and chewing insects like aphids and caterpillars. It is also a hormone disruptor and interferes in the development of the adult form. Neem seed oil and the meal are also antiseptic and antifungal, and both products are biodegradable. Placing meal on the ground protects the plants roots from grubs, root nematodes, and root aphids and, hopefully, reduces or eliminates the aphid stem mothers.

Please keep in mind that the management of the aphid colonies has to begin early in the growing season and be done before the monarchs arrive to breed, usually late summer and early fall. With careful attention, I usually manage to keep the aphids in check, but my long-term goal is to eradicate the oleander aphids from my garden by preventing the aphid mothers from over wintering.